- Acknowledgements Page -

© 2006 Andrew McQuade

Part One

Introductions and Theoretical Concepts

GENRE AND THE AUDIENCE:

PRODUCER, TEXT, RECEIVER

The idea for this research

project began when I read Rick Altman’s Film/Genre some years ago. In

his book, Altman gives a highly comprehensive insight into the concept of

genre in relation to film. He traces the concept of ‘genre’ back to

pre-literature and attempts to give an overview of the evolution of the

concept, ultimately leading to our current understandings of the term.

Chiefly, he examines the institutional requirements and benefits of ‘genre’ as

a marketing tool, and in particular the role critics play in shaping genres

over time. For Altman, genres are chimera entities, forever going through a

process of commercial recycling.

Altman’s book raises the

question, ‘if a genre cannot be said to be an objective construct, rather a

complex social construct that occurs over time, how can it possibly be useful

to commercial investors let alone scholars?’ Wouldn’t producers logically

prefer to invest in ‘solid’, ‘dependable’ and ‘objective’ projects rather than

some obscure pro-morphic entity? Whilst scholars have celebrated poly-generic

texts, from various theoretical perspectives, this has often led to a lack of

concern towards a text’s institutional requirements. For example, a film may

be abound with elements of genre mixing, which may receive artistic praise

from scholars using auteur theory, however, we must bare in mind that any

‘artistic’ auteur still has to fit industry standards. They still have to make

money and work as part of a huge team, through the many stages of production.

In Altman’s view, the role of

the critic is to shape the way genres are received, for it is their

‘enlightened’ perspective on a film’s ‘objective properties’ that ultimately

prepares, or suggests, interpretative viewing strategies for the consumer. For

Altman, genre today is a constant reinvention process, where ideas are

recycled rather than an invented (Altman, 1999: 34), but he does not comment

on how this affects the interpretational strategies of the folk consumers.

Altman deals with the ‘film’ in

Film/Genre more than the ‘genre’. This made me wonder, if we take

Altman’s ideas to another medium; are the roles of industry and critic so

pronounced, and do they function in the same way? The critic and the marketers

may shape the discursive framework by which generic texts appear in the public

sphere to an extent, but what input does the consumer have and what of a

text’s creators? Are they no more than names on a poster, dehumanised into

nothing more than figments of some capitalist agenda? Altman employs no

audience research to give insight into their particular input into ‘the genre

game’. Rather, they are there, by implication only, to consume both the text

(as supplied by the producer) and the context (as decreed by the critic and

marketing forces). Altman neglects, as does so much genre theory, the

vernacular. The day-to-day folk who consume texts, their vernacular theories

about them and practices of consumption, are ignored and the relationship of

these folk to a film’s producers is textual at best.

Thomas McLaughlin parallels

vernacular theories to Foucault’s “subjugated knowledges,” those knowledge

types that are subject specific, but not to the established standards of the

hegemony (McLaughlin, 1996: 7). Not only are the folk consumers ignored though

in Altman’s theory, I would argue that the producer of a text has become

naught but a dehumanised industrial construct. The vernacular does not apply

solely to audiences, as subjugated knowledge types occur everywhere in our

society, including producers. McLaughlin calls this particular knowledge

‘insider theory’ (McLaughlin, 1996: 102).

Why should any of this be of

interest? Within popular music, the grunge movement appeared in the late

eighties in stark contrast to ‘poodle hair rock’ which dominated the

mainstream at the time. We can surmise, or theorise as some academics have

mislabelled it, that grunge’s popularity was due to its counter-mainstream

aesthetics, but without being within the musical culture of the time, we can

do no more than surmise. We need to understand the consumer viewpoint from

within, to find out why it is that such seemingly random genres appear from

out of nowhere and find success, but we also need to understand the

perspectives of such bands themselves.

Ethnography has proved a

popular method of scholarly enquiry when investigating culture and

sub-cultures of all types. A record company’s sales statistics may give a

quantitative indication of what is popular, but they can never explain why.

Karen Halnon, in ‘Inside Shock Music Carnival: Spectacle As Contested

Terrain’, uses multi-textual ethnography as a means to discover what the music

of ‘carnivalesque bands’ such as Slipknot and Insane Clown Posse mean to the

fans themselves, and how such music is important in their every day lives and

is important in their formulation of self identity through ‘commodified

rebellion’(Halnon, 2003: 774). Importantly, Halnon’s investigation is one that

uses interview excerpts to back up her claims, not just random theorising. The

every day meanings within a culture, such as the ones Halnon investigates, is

something ethnography seeks to understand. For Spradley:

The essential core of ethnography is this concern with the meaning of actions

and events to the people we seek to understand. Some of these meanings are

directly expressed in language; many are taken for granted and communicated

only indirectly through word and action. But in every society people make

constant use of these complex meaning systems to organise their behaviour, to

understand themselves and others, and to make sense out of the world in which

they live. These systems of meaning constitute their culture; ethnography

always implies a theory of culture (Spradley, 1979: 5).

Halnon, a fan of many of the

bands whose culture she investigates, uses excerpts of bands’ lyrics to

demonstrate how they allow fans to identify with a band, which helps in the

fan’s formation of self identity. She validates this against interviews with

several concert goers at ‘carnivalesque’ music festivals. However, by only

examining the thoughts of festival participants, that suggest the musical

performers themselves are mere textual facilitators. They are almost

culturally extradited as human beings, representing only ideologies through

‘spectacle’ (Halnon, 2003: 751 – 753). This is a problem that needs

addressing. Referring to online fan groups, Nancy Baym notes that

“[s]cholarship so far has barely scratched the surface of the interplays

between media producers and online fans” (Baym, 2003: 247). Jenkins suggests

that “[r]ather than talking about interactive technologies, we should document

the interactions that occur amongst media consumers, between media consumer

and media texts, and between media consumer and media producers” (Jenkins: n.d.)

As such, this Dissertation asks ‘what can be learned by looking at

producer/consumer relations in cyberspace?’

Reception studies emerged

partially as a reaction against dominant forms of textual analysis, where the

scholar’s enlightened wisdom would unlock the hidden meanings of a text. By

placing the emphasis less on the texts ‘intrinsic properties’ and more on the

marketing of texts and what texts mean to audiences, a greater level of

meaning could theoretically be unlocked which was not subjective solely to the

scholars’ interpretation (Staiger, 2005: 3). However, this shift in emphasis

occurs for reasons of practicality also, which are seldom admitted. A scholar

investigating the release of War Of The Worlds (Spielberg, 2005) cannot

just call up the director and ask him questions about the texts production. As

such, scholars practising Reception theory, such as outlined in Staiger’s

Media Reception Studies, can only examine the last few parts of the chain.

This has led them to imply the needs of the textual producer without any

verification at all, just as textual analysts fail to verify their claims with

actual audiences. We need to look at both producers and consumers to readdress

the balance.

The problem with such a

proposition is the amount of variables it requires the researcher to be in

control of. It requires the researcher to be present at the birth of a new

stylistic genre movement, to be able to integrate into the culture surrounding

it, and to be able to research it competently by having access to text,

consumer, and producer. Luckily, I am in such a position. The Swedish band

Machinae Supremacy (or ‘MaSu’ as abbreviated by their fans, hence the term I

shall use) achieved great success at an underground level in the five years

since they started making music. They produce a style of music that is

recognisably rock orientated, but distinctly different from other styles in

either the mainstream or the underground, incorporating musical influences

primarily from computer games.

I do not claim their music is unique from a musical theorist’s perspective,

and I should stress that my theoretical background is not within this field.

This claim I make from my own vernacular knowledge of rock/metal culture, but

as I hope to demonstrate later in my research, this view is more than verified

by other members of MaSu’s fanbase. I wanted to find out how and why a band

that plays a style so generically unlike other bands has gained a loyal

fanbase, by examining the producer/consumer relationship, shifting the

emphasis away from the textual elements except where referred to in

producer/consumer discussion.

With so many independent

musicians, film makers, and other artists turning to the Internet to express

their creativity, I hope my research will be able to demonstrate how artists

can be successful independently in new media environments, and that aesthetic

conformity to the standards of the industry need not be a pre-requisite. Such

research then, is of more than just academic importance.

My Dissertation is split into

three key sections:

- In part one, an overview of

various theoretical issues which first need to be addressed.

- In part two, I will consider

the results of the ethnographic part of my investigation. Using virtual

ethnography (sometimes referred to as ‘cyber ethnography’). The object being

to understand the band’s reception by looking at producer/consumer

interaction.

- In part three, my conclusion

will highlight what has been learnt by ethnographically looking at online

producer/consumer relations.

ETHNOGRAPHIC BOUNDARIES, ETHICAL ISSUES, ONLINE SOCIAL

HEIRARCHY AND ‘HCMC’

What makes MaSu so accessible

to an Audience and Reception Studies scholar is their almost exclusive online

marketing. The band have made hundreds of free mp3’s available on the

Internet, done online interviews, participated in IRC

sessions, and they host their own forum where they interact with their growing

global fan base. They have openly allowed fan production including desktop

wallpapers and song remixes. They engage in discussions with their fans on a

wide variety of topics not always musically related. With the Internet so

vital to the band’s reception, they are a highly practical research entity. As

Christine Hine suggests:

The ethnography of the Internet does not necessarily involve physical travel.

Visiting the Internet focuses on experiential rather than physical

displacement. (Hine, 2000: 46)

As a researcher I can access

the majority of the band’s musical texts legally via mp3, and view/participate

in social interactions, on the official forum. The MaSu official forum allows

for a culturally specific understanding of both sides of textual divide.

A forum is a place online where

end-users can post comments on topics of their choice in a ‘thread’. A forum

is usually designated to one parent topic, with several sub-sections

discussing various areas of said topic. Once an end-user has navigated their

way to the sub-section of their choice, they can create individual threads or

post in existing ones. In a thread, other end-users can then add their own

comments, taking discussion into directions that can sometimes be far removed

from the initial subject. Discussions on a forum differ from ‘live’ chat rooms

using JAVA script, in that forum discussions are always turn based and do not

allow for real-time video/audio conferencing. Some forums allow for anonymous

posting, but on MaSu’s forum, all end-users have to sign a ‘terms of

agreement’ declaration before joining, to make them members of this ‘virtual

community’. Virtual Communities, according to Howard Rheingold, the inventor

of the term, are “social aggregations that emerge from the Net when enough

people carry on public discussions enough, with sufficient human feeling, to

form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace” (Rheingold, 1993: 5). As

such, I am working from the concept of the likes of Anderson, that communities

do not require face-to-face, or rather body-to-body interactions. Communities

exist in the conscious, rather than the physical (Anderson, 1983: 18).

Much of the issue’s around

Internet research ethicality centre around the ‘Internet as public versus

private zone’ debate. The forum is a public zone and all chat that occurs on

there can be considered ethically researchable, based on the fact that

end-users can choose to send private messages to each other, which are not

viewable by the public. This means that whilst some data is always concealed

from the ethnographer, since this data is sent privately, it would not be

ethically researchable anyway (Stern, 2003: 251). I have divulged some private

messages addressed to me during this research, because they were at my liberty

to reveal and did not contain anything incriminating about the end-user who

had sent it to me. It is impossible to provide citations for these comments as

they are only accessible from my personal log-in, but in orally based

ethnography such citations are rarely available at all, beyond the word of the

scholar.

Whilst not all forums are

designed for leisure purposes, in the case of the MaSu forum, this

cyber-environment fits Radway’s description of the ‘leisure world’, being

“conceptualized as sites for the pursuit of what are still referred to as

‘merely’ hobbies or avocations, they are increasingly and ironically the very

realms in which individuals invest most of their energy, money, and time” (Radway,

1988: 370). Building on the concept of the Internet as hyper-real, or

hyper-textual, environment (Livingstone, 2004: 80), we can see forums as

‘hyper-leisure worlds.’ Because of MaSu’s presence on the forum, these leisure

worlds can also been seen as the site of producer/consumer vernacular

relations. Radway seems to hint at the significance of this in the closing of

her essay, when she questions “perhaps it might also be possible to identify

together those points where articulations and alliances could be forced across

the borders in the service of a future not yet envisioned and therefore

neither necessarily lost nor secured” (Radway, 1988: 374).

Dennis Waskul and Michael

Douglas, in ‘Cyber-self: The Emergence of The Self in On-line Chat’ use the

term ‘cyberself’ to refer to the self identity of the end-user and suggest

that “a cyberself is always whatever is passing for a self at the moment in an

electronic-computer-mediated context” (Waskul & Douglas, 1997: 375) From a

research ethics point of view, end-user anonymity is of vital importance. Were

it possible to trace an end-user’s comment to their location in the offline

world, an ethnographic investigation such as mine could not take place.

Fortunately, the IP address of an end-user’s computer is not accessible to

other end-users on the forum. End-users are in control of how much information

they reveal about their ‘real identity’, and any incriminating information I

have not included in this paper. I do not regard any of my research as

harmful, nor would I conduct it if it was, thus the ethical issue of

dishonesty/harm is not present. I made end-users on the forum aware that I was

in the process of writing this paper.

A ‘moderator’ is an end-user

selected because they appear to be capable of holding a responsible position,

and who is entrusted with more power than standard end-users. Such powers may

include the right to close threads indefinitely (‘locking’), censor comments,

and even ban users if comments are derogatory or discriminatory. Depending on

how strict a forum is, moderators can also make sure discussions do not stray

from the initial thread topic. In this respect, they direct the flow of

end-user exchange to a degree.

All forums then, have power

relations and social hierarchies like in the ‘real world’, however they are

not necessarily alike the ones in the real world. Within virtual ethnography,

traditional social norms become contorted and the participant/observer duality

becomes much more confusing as the line between reality and hyper-reality

becomes increasingly blurred. An end-user can be logged in for hours and never

make a single comment, thus being present within the folk group of the forum,

but not contributing to human computer mediated communication (HCMC).

This is known as ‘lurking’.

It is arguable that simply by

the scholars presence, he or she is contorting the social world, so as to

create records that do not capture the ‘natural cultural environment’.

‘Lurking’, if we follow said logic, is a method by which to observe social

interaction without such ‘contamination’. I take issue with the notion that

there can ever be such a thing as ‘naturally occurring’, or ‘intervention

free’ data. Not only is the word ‘natural’ extremely ambiguous and wrapped in

ideological assumptions, but in my instance, I have been a member of MaSu’s

forum long before I began writing this Dissertation. For me to not be

interacting on the forum would be equally corruptive to the so-called ‘natural

order’. Ethnographically speaking, to extradite myself experientially from

social interaction would be to not fully capture the vernacular meanings of a

culture, which would be methodologically un-sound.

Henry Jenkins’ investigation

into the alt.tv.twinpeaks newsgroup is one of the pioneering investigations

into online fan culture and consequentially HCMC. In his piece, Jenkins

focuses on the HCMC elements most akin to normal talk though. That is to say,

text is just seen as text, with little mention of the way text is contextually

altered by the advent of the Internet. Nonetheless, his investigation has been

particularly influential for me, in the way he picks out key motivating themes

and ideas that appeared in the HCMC he observed. In his work, some end-users

suspected that Twin Peaks creator David Lynch was present on the

newsgroup and trying to mislead them (Jenkins, 1995: 59). Here the

producer/consumer relationship is implicitly acknowledged. In my research, it

is explicit by virtue of the fact that MaSu themselves are active members of

their forum.

The problem with ‘text centric’

interpretations of HCMC is that, like in discourse analysis, the visual cues

are filtered out. Whilst an end-user is never aware of other end-users facial

expressions like in oral communication, words accented or written in capitals

take on different meanings online. In addition, forum avatars,

signatures,

use of visuals and sound are all elements contributing to HCMC and an

end-users online identity. The semantic dimension of HCMC is not the same as

in the ‘real world’ and an online ethnographer must be aware of this. Virtual

ethnography is about more than just simulacrums of ‘real’ language.

I do not wish to suggest that

MaSu are not discussed elsewhere on the Internet besides their forum as they

are discussed on other forums relating to the rock/metal spectrum as well as

forum relating to gaming culture too. However, the potential number of sites

hosting HCMC discussions exceed the thousands, and it is virtually impossible

to find the online locations in which the band have been discussed. Ultimately

though, their official forum is the only place I can research

producer/consumer HCMC exchange. My research into MaSu often led me to look at

other related websites cited by the folk of the forum. I do not see this as

transgressing the ethnographic boundaries I have placed, by researching

outside the forum. Rather, in viewing other MaSu related sites, such as their

unofficial FAQ, I am participating in an activity shared by other members of

the online community.

I already have a certain level

of vernacular knowledge of what it means to be a MaSu fan and there is a

danger of taking for granted issues which should be subjected to ethnographic

scrutiny because of this. However, I believe my vernacular knowledge about

MaSu means I have less gratuitous amounts of new information to take in,

compared to someone completely alien to the band. A major benefit of the

ethnographic approach is that it removes the ‘clinical’ nature of the focus

group and provides greater potential for the scholar to be genuinely immersed

in a cultural environment, rather than moderating a discussion from some

mythic ivory tower of academia. Whilst it is theoretically possible to use a

forum as an online focus group, this requires the scholar to behold the power

of moderation, thus drastically altering social hierarchy. The results is that

a focus group can certainly examine the vernacular, but it cannot experience

it. To understand a culture from within, it is necessary for the scholar to be

on the same level as the folk. Schrøder et al, in Researching Audiences

summarise the Malinowskian position that:

[T]he ethnographer should study culture not just from a bottom-up perspective,

but from an insider’s perspective, an aim that demands committed, long-term

immersion into a setting in order to understand how meaning is achieved and

attained. Moreover, the ethnographer should study culture from a holistic

perspective (‘his world’), an aim that demands equally committed analysis of

multiple view and often contradictory sources in order to understand how

meaning is constituted as contextualised practices (Schrøder, 2003: 65).

As such, we gain more from

seeing the producer/consumer interaction as being from different sources

within the same cultural sphere, rather than intrinsically oppositional. This

pre-determined opposition between fans and producers, as seen in other work on

fan culture, I take issue with. I will outline why in the next section…

HENRY JENKINS, THE GUERILLA AUDIENCE, AND THE

POST-MODERN VISION OF ‘THE INSTITUTION’

Be it a ‘dot com’ mogul, record

producer, or a film company; in all such instances the ‘producer’ is usually

seen from a perspective that projects the image of the greedy capitalist

producer who relates to the consumer only as a human embodiment of financial

capital.

An example of the ‘producer

versus consumer’ relationship is echoed in the work of Jenkins, who in

Textual Poachers, brings up this issue in his in-depth discussion Star

Trek fans and their production of ‘filk’ texts, noting how fans rebuke

established power relations in producing their own fan-fiction. Employing

DeCertauian ‘tactics’ (as opposed to the ‘strategies’ of the empowered

institutions), fans produce texts that develop ideas and character

relationships not seen in the TV show (Jenkins, 1992: 33). These fans

selectively poach from official texts to satiate their own needs. Jenkins’

view of the producer/consumer relationship is a step up from the factory

worker being exploited by the corporate ala Marx, but Jenkins still sees the

fans relationship to the producer as defined by resistance to the hegemony

(Jenkins, 1992: 40).

Barker, in Knowing

Audiences: Judge Dredd, speaking of pre-deterministic social research,

notes that “[t]here was research which seemed to show that witchcraft existed,

and which had powerful effects – but in the eyes of those who scorned and

attacked it, that was because it was so designed that it was bound to find ‘witches’”(Barker,

1998: 84). By selectively looking for information with a set interpretative

strategy at the ready, witchfinder generals parallel some academic researchers

more often than we would like to admit. Whilst Jenkins’ insights are valuable,

and may well be correct in regard to the fan group he investigated, he is

guilty of never looking at the other side of the textual wall. By seeing the

producer/consumer as two entirely segregate entities operating within the same

sub-culture but diametrically opposed to one another, a relationship is

imposed on them, which has resulted in a producer/consumer relationship within

fan studies as being pre-determinately hostile. Radway seems to advocate

readdressing this balance throughout her essay ‘Reception Study: Ethnography

and The Problems with Dispersed and Nomadic Audiences’, stressing the need to

examine producer/consumer relations, noting that “[t]o think of someone as a

listener or receiver in an audience, obviously, we must first assume the

existence of the speaker/producer” (Radway, 1988: 361). More importantly,

that; “the words separating ‘us’ from ‘them’ are not natural boundaries, but

social borders of our own making” (Radway, 1988: 374). However, as she further

outlines her research proposal, it appears that she too predetermines the

producer/consumer relationship from the outset:

I suggest a study of the production of popular culture within the everyday as

a way of trying to understand how social subjects are at once hailed

unsuccessfully by dominant discourses and therefore dominated by them

and yet manage to adapt them to their own other, multiple purposes and even to

resist or contest them [my italics] (Radway, 1988: 368).

Whilst I am not attempting to

discredit the work of those theorists who have looked at how audiences reject

‘hegemonic meanings’, I would argue that the issue of ‘meaning’ itself has

become less a case of semantic interpretation, more a case of semantic war.

The work of Fiske has been particularly influential in advocating this

perspective, but as Dhalgren notes “he makes too much of the ‘resistance’ to

hegemony that alternative interpretation of popular programmes might entail” (Dhalgren,

1998: 300). Further noting that “[O]ne’s point of departure and interests

shape to some extent the notion of ‘audiences’, and one thus conceptualizes

‘audiences’ within particular discursive settings” (Dahlgren, 1998: 307). I

would suggest that the language of warfare, epitomised by the likes of

DeCerteau’s ‘Guerilla viewer’, does not generally reflect fan culture from a

fan’s, or even producer’s, point of view.

Textual Poachers

drastically changed previous academic preconceptions that fans were nothing

but passive, if slightly quirky, textual consumers. However, the dualistic

division between Star Trek’s producers and its fans, as Jenkins sets

them up, puts them in opposition to the extent that one would almost be

inclined to believe the makers of a show like Star Trek had no interest

in the show at all. In seeing fans as passionate, intelligent, and committed,

the producer, by contrast, has become a tyrant. There are several possible

reasons for this, and I would suggest that the main one is the dominant

modernist perception of the institution. The producer/fan oppositional

relationship is essentially a modernist construct. With modernisms need for

hierarchies, social order, definable boundaries, constant and objective

segregation, a producer/consumer relationship characterised by conflict does

not seem an unlikely outcome. The reason being, that the ‘organisation’ is so

vast, so concerned with its own structure and segregation, that the consumer

can only exist as a commercial statistic (Styhre, 2001).

Styhre, in ‘Nomadic

Organization: The Post-modern Organization of Becoming’, discusses the

‘nomadic organisation’ as one that is constantly on the move, always seeking

to branch outwards, not constricted by boundaries, and, perhaps most

importantly, where the boundaries between the internal and external become

blurred. As he notes:

In a post-modern capitalism, there are nothing but fluxes, breaks, changes,

and bifurcations; the organization thus becomes an open system with close

relations with the environment. The boundaries between inside and outside are

continuously transgressed. As a consequence, a pluralist epistemology of

becoming is needed, an epistemology that acknowledges a polyvocal and

polysemiotic view on the organization (Styhre, 2001).

Whilst I would not go as far as

to call MaSu a ‘nomadic organisation’, there are clear benefits to Styhre’s

model. In such a model, the producer and the consumer are no longer at war on

the battlefield of textual production/consumption. The Internet has forced

scholarly redefinition of social boundaries and problematises modernist

notions of segregation, with its blurring of real and hyper-real environments

(Waskul & Douglas, 1997: 378 – 379). It openly allows for such a post-modern

view of the organisation. Whilst Styhre still seems more concerned with the

modernist view of the ‘mammoth organisation’ in his piece, he at least affords

the potentiality to see the organisation as something other than

Godzilla-like. The institution can conceivably be a ‘local’ phenomenon. With

the fan already established as an example of Foucault’s ‘localised power’ or

Tulloch’s ‘powerless elite’, we can now see the creator of a text and the fan

as compatible entities, with the producer not necessarily exclusively

segregated by capitalist prerogatives as he/she/they sit in a gigantic

skyscraper.

Even with Styhre’s model, it

would be foolish to suggest Jenkins’ research and mine are directly comparable

for there is a big difference in scale. Star Trek is a mammoth

enterprise with directors, writers, producers, marketing people, and Paramount

Pictures executives all involved in the process of turning the Star Trek

name into profit. It fits the modernist model perfectly. MaSu, conversely,

sell all their own merchandise through their own label ‘Hubnester Industries’,

accessible online. They are textual producers, performers, money men, a rock

band and rock fans all at the same time. This is not to suggest hierarchy is

suddenly extinct in the world of MaSu, but it does not exist exactly like in

Jenkins’ example. MaSu are subject to copyright just as much as Star Trek,

but we need to conceive the potentiality of a producer/consumer relationship

that can be more intimate, a horizontal relationship as well as vertical, not

just the latter.

Critics of this position would

no doubt point out that an intimate producer/consumer relationship is

farcical, an illusion brought about by the identity of the ‘end user’ within

new media. It is capitalist greed under a newer, more technologically friendly

guise, fooling end-users into thinking they have more power than they do

(Weinstein & Weinstein, 2000: 200). Within the technocapitalist model of Best

and Kellner, such a position is certainly viable. In their model, the Internet

allows the previously impossible potential for unlimited and rapid trade (Best

& Kellner, 1997: 58). The producer/consumer relationship is defined by low

cost production, but high financial intake at unprecedented speed (Styhre,

2001). The model suggests rapid-fire capitalism is the sole benefit of new

communication technologies, with the distance between producer and consumer

kept the same as in other traditional modernist models. It does not consider

that new technologies bring greater communicative discourse into play, in

addition to faster exchange of commodities. It has almost become second nature

to see a capitalist model as being devoid of human interaction at all, let

alone a realm in which the term ‘vernacular’ seems applicable.

Whilst it may be true that

categories like ‘producer’ and ‘audience’ are created through the process of

production/consumption (Hine, 2000: 38), within different theoretical

discourses, these can carry very different meanings. The ‘producer’, the

‘industry’, the ‘institution’, and the ‘organisation’ all carries the image of

some mammoth, almost mythic, monster whose appetite for consumer exploitation

is insatiable. Whilst audiences have long since been liberated of their

damaging image as mere passive mass consumers of texts, the producer is still

a very ambiguous term, and one that nonetheless carries predominantly negative

connotations, particularly to those with Marxist leanings. For the purpose of

this Dissertation, let us see the following terms defined as overleaf:

·

The producer from here on refers to the textual producer. In the

case of MaSu, they are their own marketing force, musical performers,

moneymen, and function in several other roles. The producer here encompasses

all these.

·

The end-user is a particular type of audience which should not

be confused with the ‘mass’ television audience, nor should it be confused

with the individual novel reader (Livingstone, 2004: 75 – 77). Where forums

are concerned, the end-user is an active participant in the creation of a

textual world. There is no passive end-user, for even the ‘lurker’ practises

computer mediated interaction of a kind. It differs from previous notions of

the audience in that whilst the end-user is situated within the ‘real’

offline, he/she appears online as a simulacrum of the ‘real self’ within the

hyper-real environment of the Internet (Waskul & Douglas, 1997: 380).

Having established the

necessity for an ethnographic approach, the following issues need to be

investigated by looking at the MaSu community as a whole, not treating

producers and consumers as separate social entities within one virtual

setting:

1.

How important is the forum in establishing and maintaining

producer/consumer relations?

2.

What vernacular discourses mediate on such forums and how are they

maintained?

3.

What is the significance of ‘genre’ as a discourse?

4.

What are the etic/emic qualities within the MaSu online community?

5.

How does talk around the discursive object (the band) function within

the forum environment, how are opinions expressed, and what areas are taboo?

6.

What social hierarchies are observed and how do/don’t these differ

between producer and consumer?

Within any research practise,

the position of the scholar is one that inevitably affects results. Even those

scholars who insist absolute objectivity is attainable would admit the

presence of the researcher always has a bearing on what is being researched.

For a scholar participating in an ethnographic study of fan culture, the issue

of being too immersed or too close to the discursive object is a problem often

debated. In the next section, I will discuss where I position myself within

the fan/scholar debate, my relationship to the band, and what I see can be

gained from this.

THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY or THE FAN/SCHOLAR,

THE SCHOLAR/FAN, AND THE POST-GRADUATE SOMEWHERE IN THE MIDDLE

In participant observation, the

dangers of being too close to the research object mean that research could be

flawed if the scholar is not able to mediate between participating in a

cultural setting and observing it to the correct degree. Where the ‘correct

degree’ is exactly, is of course subjective and appropriate to the uniqueness

of each cultural encounter. Ethnography complicates this even further, by

requiring the scholar to see things through the eyes of cultural participants

themselves. It incorporates an experiential dimension to the proceedings,

which is an integral part of meaning making. When studying a fan culture,

there is the added problem of the scholar already having personal investments

in the object of study and even pre-existing investments in the culture being

studied. I hold no delusions that I am exempt from these issues and thus need

to address them, my place within the scholar/fan dualistic argument, and my

views on what Matt Hills refers to as the inevitable ‘imagined subjectivity’ a

scholar in this situation faces (Hills, 2002: 3).

For Hills, the fan/scholar

dynamic is one characterised by a dualism that is not clear-cut. Where most

scholars perceive this dualistic divide purely from the academic perspective,

Hills suggests that fans too are aware of the divide, which leads many fans to

be sceptical and even cynical of academia. For Hills “[s]uch marginalisation

would suggest that fandom and academia are co-produced as exclusive social and

cultural positions” (Hills, 2002: 2). On both sides of the divide operates an

‘imagined subjectivity’.

For the scholar “[i]magined

subjectivity, we might say, attributes valued traits of the subject ‘duly

trained and informed’ only to those within the given community, while

denigrating or devaluing the ‘improper’ subjectivity of those who are outside

the community (Hills, 2002: 3). But as he notes, this devotion to rationality

and persuasion is contradicted by the multitude of opposing positions taken

with academia. Meanwhile, the fans ‘imagined subjectivity’ places him/her in a

position where he/she cannot account for his/her devotion to whatever the

object of their fandom is (Hills, 2002: 7). Such skills are only possessed by

the ‘good’ academic. I would suggest it is a gross estimation to perceive fans

are incapable of accounting for their devotion to a text, or that academics

are always able to articulate their pop-cultural investments with critical

distance. This implies all Academics have the ‘skills’ of those operating

specifically within the social sciences, which is not true.

McLaughlin in Street Smarts

And Critical Theory notes that fans often theorise in the same ways as

academics (McLaughlin, 1996: 6), but in a different cultural environment, with

what could be described, by the likes of Hills, as ‘different tools of

subjectivity’ to the scholar. Hills takes this a step further, suggesting

academic criticism can appear in fan discussions in the character of the

fan-scholar.

Hills’ comments on Steven

Frith’s important 1992 distinction between the ‘intellectual’ and the

‘academic’, identifying that whilst Frith suggests a distinction between the

two, he in fact uses the terms interchangeably (Hills, 2002: 6). However at

the same time there is ambiguity in Hills’ writings as to what ‘scholar’

means, versus ‘academic’. Within either fan-scholar discourse or scholar-fan

discourse, these lexemes seem to take on different meanings. ‘Scholar’, in my

understanding, refers to anyone using academic theory. Within ‘fan-scholar’

discourse, these are often ‘elites’ within fan culture. The ‘academic’ is

defined by a purely institutional position. As Hills notes though, both groups

share the same traits, the primary noun in the set defines the social

discourse by which action follows. For example, the academic-fan will not use

the same language in a lecture as a fan-scholar at a fanzine convention

(Hills, 2002: 20).

Hills finds it inevitable that

fans and academics oppose each other, because of the academic’s need to

‘translate’ vernacular theory into ‘proper’ theory. There is a gap here

however. Though Hills acknowledges there are fans who use academic theory,

many of them being ex-media studies for example (Hills, 2002: 18), he makes no

mention of where the undergraduate or postgraduate student fits in to his

work. Are these no more than fan-scholars simply because they do not work full

time in an academic institution? If the issue is not of knowledge, but of

social discourse, as is the running theme in Hills’ argument, this cannot be

so. The ‘student’ is a different social discourse to the ‘academic’, which is

different to the ‘fan’.

During my time on MaSu’s forum,

I found that I was one of many students (albeit the only one actively

researching MaSu). The fans did not ‘other’ me, or become intimidated by my

academic prerogatives, as Hills argues they are pre-determined to do. Rather,

in cases, they were enthused about my research and often wanted to know more

about it. The label of ‘student’ is different to the label of ‘academic’. It

affords the potentiality of an academic intellectual capacity, but without

being institutionalised. This affords me a greater level of mediation between

scholarly and fan prerogatives, for I am neither of these full time and am

subject to the corresponding associated social discourses only as and when

required. Whilst Hills is right to point out that vernacular knowledge needs

to go through a process of ‘translation’ to be useful within an academic

context, his argument that you are one or the other, with only an imagined

subjectivity as catalyst between the two, is uneven and I would suggest that

attempting to fit everything within a model of dualism is an inefficient

academic explanatory strategy.

This Dissertation is not a fan

study. Fans are but one particular social identity present on the MaSu

official forum, with a whole set of other identities, with complex social

relations, integral to the community. These dynamics, amongst many other

topics, I explain in Part Two.

Part Two

An Ethnographic Investigation of ‘forum.machinaesupremacy.com’

INTRODUCING

‘forum.machinaesupremacy.com’

When practising virtual

ethnography, one needs to first decide whether one is investigating the social

interactions conducted on the Internet directly, or the way in which social

mediations made practical by the technological advances of the medium itself.

The study of interaction between human and machine is termed ‘cyborg

anthropology’ by David Thomas, which can include interactions with other

humans when mediated through computers, but the emphasis is on human/machine

relations directly (Escobar, 2000: 62). Whilst this Dissertation is concerned

with more anthropocentric interactions, issues of medium and environment do

need to be addressed. Before I can discuss the producer/consumer dynamic of

the forum, and the presence of genre discourse therein, we first need to look

at issues such as:

- How the Internet changes

social hierarchical formation processes.

- How the social relations on

MaSu forum require us to reconceptualise the producer/fan dynamic.

- What forms of knowledge are

culturally specific to the MaSu forum.

From there we can address the

issues I put forward in Part One of this Dissertation. I have devoted a

section of Part Two to each of these issues.

Throughout this section I will

be referencing various sources of information collected

online. Some of these refer to

HCMC on the official MaSu forum, others cite websites such as the unofficial

MaSu FAQ and ‘Wikipedia’. In the case of the latter, data was small enough in

quantity to be able to print off and include in appendices (1) and (2). These

sources are notable because they exhibit useful vernacular knowledge about the

band, but also because they summarise the band’s history, providing a good

biographical introduction to MaSu if preferred by the reader.

When quoting end-users, I have

not acknowledged nor amended grammar inaccuracies. Online grammar differs very

much from offline grammar and to highlight online inaccuracies through the

lens of an offline scholar would be ethnographically un-sound. I have noted

edits however.

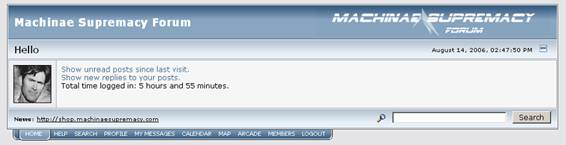

Figure 1, shows a screenshot

from the official MaSu forum homepage, the gateway to the virtual-community

upon which the majority of this Dissertation is based.

In figure 1 several major

headings can be seen, such as ‘The Band’, which is then further divided into

sub-headings. These are sub-sections of the forum in which one finds

individual threads. When sub-sections are broken down they form a chain such

as: ‘Machinae Supremacy Forum > The Band > The Music > The Newbies Guide To

Frequent Topics’. When referencing a thread, I refer to the last link in the

chain, the full citation of which is located as a footnote. Methodologically,

there is still no one approved way of analysing web-design, much less forum

layouts. However, where certain sub-sections on a forum are arranged can tell

us a lot about the discourses operating within a forum. For example, ‘The

Band’ includes two sections: ‘The Music’ and ‘Arcade’. ‘The Music’ is the most

active section of the forum, with more new threads appearing in here than any

other section. Under ‘The Music’, end-users can discuss the band’s music, like

we might expect on any rock band’s forum. ‘Arcade’ is an area designed for

discussion of computer/video games across all platforms.

By putting the sub-section ‘Arcade’ under the heading ‘The Band’, a link is

suggested between MaSu and computer/video gaming. The ‘Off Topic’ area is also

split into two sections. ‘General’, is for discussing anything unrelated to

MaSu or gaming. MaSu can still be mentioned here, but topics do not generally

concern them. The ‘Musicians Section’ is where end-users can talk about their

own music and the problems of recording, writing, singing, and playing music.

It differs from the ‘The Music’ thread because it does not relate specifically

to MaSu’s music, but the fans’ creations. Discussions are sometimes referred

back to MaSu here. In numerous instances end-users would ask how a particular

sound was achieved on a particular MaSu track. In such cases, these are

discussions of MaSu on a musically technical level, rather than as a leisure

interest. MaSu become an object of comparison for the folk to aid them in the

production of their own music. For example, in ‘Question

for the band (specifically Robert?)’, an end-user asked the band themselves

about a particular vocal affect he wanted to recreate:

On the Song "Gost (Beneath the Surface)" I'd really like to know how you did

the vocal effects. I've been trying to figure out how you do that, because

I've heard it in a few of the band's songs before, and all attempts at

recreating such an effect have failed. It's like a reverse echo/fade in on the

vocals. "I stand still out in the rain......" How it fades it on a reverse

echo on that part.

The band replied, and throughout

the thread they advised this end-user how best to recreate the desired sound

for his own music:

Well... I dabble with chorus, flanger, delay, and

more than once during the process i reverse the take and process it

backwards...

Nothing advanced, you'd probably be able to do that with one chorus plugin and

one delay plugin... Not counting EQ, of course.

The ‘Contribute’ section

contains an area for uploading guitar tabs of MaSu songs made by fans, and

also a section for uploading gig photos and videos.

Music ‘Tabs’ have their own

sub-section, implying a distinction from the previous two musically related

categories. This sub-section is for musicians who specifically want to be able

to learn to play MaSu songs, demonstrating that the band is actively

encouraging fans to make their own tab transcriptions of their music. Such

transcriptions might be referred to as ‘fan texts’. These are distinct from

‘poached texts’, as in Jenkins’ description (Jenkins, 1992: 28 – 33), as

‘poached texts’ imply a contortion in design from the hegemonic text, which in

MaSu’s case is the music they’ve released on CD or hosted on their website.

There are no ‘official’ transcriptions provided by the band, but the process

of creating a 100% accurate tab transcription is done by the fans with aim to

create a substitute for such ‘missing official’ transcriptions, not to contort

the original song.

The producers, in this

instance, facilitate both the primary text upon which tabs are based, but also

the social space in which transcriptions can be made available to the rest of

the MaSu online community. This section of the forum, in addition to the

‘Musicians section’, rebukes notions of the producer attempting to control fan

production. The official text and the fan text run side by side, not just in

the case of music tabs, but other fan creations like desktop wallpapers and

even covers of MaSu’s songs. I asked the band to clarify their position on

this particular issue, to which lead singer/guitarist Robert Stjärnström

replied:

We totally support fan creations. The fact that fans dedicate such time and effort into such things is purely positive, in my opinion. sometimes the result is some horrid

bastardisation of a song, and then it's almost painful, but it's still a good thing.

The final two areas of the

webpage are fairly self explanatory – ‘Forum Stuff’, concerning administration

issues and where end-users can make suggestions for the future of the site,

and ‘Salvaged Messages’. ‘Salvaged Messages’ contains threads from the

previous incarnation of the forum (before MaSu’s website was redesigned in

2006). Generally, threads from the old forum are not resurrected and newer

‘live’ threads are the most important to the community. The ‘Salvaged

Messages’ section is particularly useful for ‘newbies’ though, who want to

know about the history of the band without contributing to HCMC themselves.

This section highlights the problem of time as a discourse within forums, as

virtually any discussion can be revisited provided the thread has not been

closed or deleted.

Some end-users do not visit

particular parts of the forum at all. Most of the end-users I asked about this

said they were not interested in every section. Methodologically, I am not

concerned with which end-users visit which areas. I recognise the quantitative

possibilities of this issue, but that is outside the confines of this research

project. It is interesting to note which areas are the most active from a

qualitative perspective though. For example, ‘Forum Stuff’ is not as popular a

section as ‘The Music’. ‘Arcade’ and ‘General’ are also popular areas. The

consensus among the fans is that even though they can discuss topics other

than the band on the forum, it is MaSu that is their primary reason for

joining the community in the first place.

Having established the

structure of the MaSu forum in terms of its layout, I wish to now direct

attention towards structure of a more social nature, identifying how issues of

hierarchy and identity work online. This is necessary to gain a contextual

understanding of the discussions between producer and consumer that I shall be

discussing in depth later. All folk groups are affected by their environment

and an ethnographic investigation must account for this, whether it is being

conducted in reality or ‘virtuality’.

AVATARS, ONLINE IDENTITY,

AND HEIRARCHY

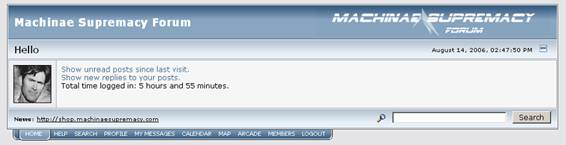

Usually the user-name of the end-user will appear next to the caption

‘hello’, as illustrated in Figure 2, beneath which, shows the avatar of the

end-user.

It is possible to change your

avatar as frequently as you like, however end-users on MaSu’s forum seldom do

this. This is unlike the practise with ‘signatures’, which are textual

excerpts that appear at the bottom of every post by the end-user. Some

end-users change their signatures frequently, either using images or caption.

When an end-user adopts an avatar however, this seems to be treated as if it

were as fixed as their user-name, even though it is easily changeable. Most

end-users I asked about this commented that it just did not occur to them to

change it. Some admitted they do change periodically, whereas others thought

it was ‘confusing’ when people changed their avatar.

Avatars themselves vary in

design from photographs of the end-users ‘offline’ self, self-rendered images,

pictures from TV/film, animated GIFs,

or anime images. Often, avatars are comic in style. The avatar image can

suggest interests of the end-user besides MaSu if they use a picture from a TV

show. My avatar was a picture from the TV show Brass Eye. One end user

private messaged (“PM’d”) me, congratulating me on being a fan of the show and

we sent each other multiple messages discussing our highlights from the show.

During the process of conducting this research, we never actually discussed

MaSu. It occurred to me here, that it was possible to be a member of the MaSu

online fan community and yet never talk about MaSu to some folk.

When I first came to the forum,

I was able to recognise some end-user’s posts, not by their user names, but by

the uniqueness of their avatar. Occasionally, avatars would be the subject of

discussion, with end-users wanting to know where another end-users design came

from. A particularly well-designed avatar is often given praise by other

members of the community. Avatars can be seen as part of a means of

establishing an online identity within a forum, which is not integral but

optional (some end-users opt not to have one). They are visual signifiers of

identity. As such, we can see that HCMC on forums is about more than just the

literally textual. I will talk more about the visual semantics of the forum in

a later section. In addition to avatars, end-users adopt symbolic user-names.

This is unlike the band, who use their offline first names, instead of

creating a symbolic ‘cyber-name’. Mine was ‘The_Holy_Ferret’.

Each end-user has a visible

status rating on the forum, and can be awarded ‘karma’ for positive

contributions to the community. These contributions can be file uploads such

as desktop wallpaper or a Winamp skin,

or simply comments thought to be exceptional within a discussion. Post counts

are also visible for each end-user. Administrators, moderators, and the band

themselves, have their own fixed status levels, although their post counts are

still visible. During the period 01/06/06 – 01/09/06, in which this research

was conducted, my status level remained at ‘newbie’, however I have since

achieved a post count in the hundreds and will soon progress onto the next

status level.

A frequent debate where online

communities are concerned is ‘how much does offline identity affect online

identity?’ Such a question is worthy of an entire Dissertation in itself,

however in the case of MaSu, it is clear that the band member’s offline

identities are highly important to the other users on the forum. Miller and

Slater, commenting on the theory of virtuality, in which the offline is seen

as not entirely independent from the online, note “that media can provide both

means of interaction and modes of representation that add up to ‘spaces or

‘places’ that participants can treat as if they were real” (Miller & Slater,

2000: 4). As such, even an offline name becomes a ‘symbolic’ name in for an

end-user’s ‘cyberself’.

It was evident that the steps

towards developing an online identity within the forum were not as applicable

to the band in the same way as they were to other end-users. For example,

their comments are welcomed more eagerly by the fanbase. Because different

rules apply to MaSu than other end-users, this implies the issue of hierarchy,

but also demonstrates the importance of the band to the forum, not merely as

textual providers but as individuals in their own right. This is not to say

there is not a fantasy element, or an element of adoration from the fans in

interacting with the band, but it does refute Hills’ arguments towards seeing

celebrities as texts in themselves. In his example, Madonna is more than just

a creator of musical texts, she is a text. This is in part due to the fact her

fans can never interact with her except from a consumer distance (Hills, 2002:

179). Such is not the case on the MaSu forum. One end-user PM’d me on this

issue, stating that:

The difference with MaSu is that they’re not up their ass like Metallica.

They’re not a bunch of guys who just make music. Because you can talk to them

and chill in the same virtual space as them, they’re people who you can

genuinely relate too. You can talk to them as a fan, but they can talk to you

back in the same lingo ya know? Like, we all have more in common than just

music. Computer games and other geeky stuff .

You don’t get that with Metallicrap.

It would be naive to suggest

that the only end-users important on the forum are the band. MaSu’s online fan

base spans across the world, with many fans unable to visit Sweden to see the

band play live. Prior to the release of the band’s new album Redeemer

(henceforth RDR), the band played some new songs live at various gigs

around Sweden. One new song called ‘Fury’ was bootlegged and a copy was

quickly available on the forum. Fans attempted to transcribe the songs lyrics

from the recording with limited accuracy, for purpose of analysis. I

contributed to the deciphering of the lyrics, debating certain words or

sections of the song which were unclear on the bootleg with other end-users.

When the album’s lyrics were finally made available, myself and the other fans

realised how inaccurate our transcription efforts had been, which then became

the subject of self-ridicule.

With ‘Fury’, the offline was

quickly assimilated into the online. Those fans with personal access to the

band offline, and who had heard the new songs, became figures of importance

because their access gave them greater knowledge than other members of the

forum. However, they only became important figures by virtue of them sharing

information. Discussions of live performances are common and even though the

forum has a specific sub-section for uploading pictures, videos, and comments

about the live shows, in the instance of ‘Fury’, the importance of hearing a

new song transgressed thread boundaries, as the fans desired to hear and find

out as much as they could about it.

The issue of ‘access’ is one

that MacDonald addresses, breaking down fan hierarchies into the following

categories:

·

Hierarchy of ‘fandom level’ or ‘quality’ – In this

instance fans are separated by amount of fan participation. Those that attend

fan conventions and the like emphasise a ‘quality distinction’.

·

Hierarchy of ‘access’ – Some fans have access to people

involved in the production of the ‘official’ item around which the fans social

discourse orientates.

·

Hierarchy of ‘leaders’ – In this instance, fandom is

broken down into smaller groups. Divisions may be geographically based,

interest, based, or based on further developed social relations (e.g.

Friendship). Within such groups, some people are delegated as leaders.

·

Hierarchy of ‘venue’ – Established when a fan hosts an

event/meeting of the fan community. This does not necessarily mean

geographically (MacDonald, 1998: 136 – 137).

Certainly a hierarchy of access

exists, but other concepts within MacDonald’s theory are problematised. The

‘venue’ is hosted by the band and to say there are ‘leaders’ is to grossly

misinterpret fan power relations. One of the benefits of an Internet forum is

that it allows people who may be easily dominated in the real world, to be

stronger in an online environment. The folk of the forum do not see themselves

as being led by anybody. ‘Fandom level’ however, is explicitly present by the

fact that post-counts are recorded and always visible.

Extensive vernacular knowledge

about MaSu demonstrates ‘subcultural capital’, in Sandvoss’ terms, which can

be related to the MacDonaldian ‘access’ category. For Sandvoss “[b]eing hip,

being in the know about clubs, records and fashion, become signifiers of

cultural status, and thus function as ‘subcultural capital’ (Sandvoss, 2005:

39). This concept opposes traditional notions of class-based systems of

capitalisation and is entirely subjective to the knowledge base of the fan.

Sandvoss’ concept of subjective

knowledge serving to designate hipness, within a social framework in which

hipness is valued over money, implies this knowledge can only serve the one

who beholds it. It is not used to help others identify what is ‘hip’, only to

be seen as being hip (Sandvoss, 2005: 39). This is not the case on the forum

though, as the sub-cultural capital held by certain fans of MaSu with ‘access’

or heightened knowledge levels are openly redistributed to the community as a

whole. It is a capital that is given away freely – an anti-capitalist

capitalism of vernacular exchange, a concept at the heart of what Tapscott

calls the ‘culture of interaction’ (Tapscott, 1999: 79). MaSu’s forum opposes

the Sandvosian position that sub-cultural capital serves only to maintain fan

power relations (Sandvoss, 2005: 40), rather it allows power relations to

exist, but they themselves are nomadic in nature. As Andrew Ross suggests, the

‘free for all’ information policy is one that originated within hacker culture

but has since spread into wider Internet culture. He notes, “[i]t is a

principled attempt, in other words, to challenge the tendency to use

technology to form information elites” (Ross, 2000: 256). MaSu’s forum then,

is characteristic of what Levy, in Collective Intelligence,

terms ‘knowledge culture’. Jenkins summarises the Levyian position:

Far from demanding conformity, the new knowledge culture is enlivened by

multiple ways of knowing. This collective exchange of knowledge cannot be

fully contained by previous sources of power - bureaucratic hierarchies (based

on static forms of writing), media monarchies (surfing the television and

media systems), and international economic networks (based on the telephone

and real-time technologies) – which depend on maintaining tight control over

the flow of information (Jenkins: n.d.).

Knowledge is not power, the

sharing of knowledge is power.

SHARED INTERESTS, SHARED

VERNACULAR, SHARED FANDOM?

Prior to the release of their

first commercial album Deus Ex Machinae (DXM), MaSu released

several ‘promo’ tracks as free downloads. Most of these songs featured lyrics,

however there were several instrumentals. Two instrumentals in particular,

‘Sidology Episode 1: Hybrid’ and ‘Sidology Episode 3: Apex Ultima’, became

objects of discussion more than the others. The ‘Sidologies’ are medleys of

computer game themes from the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, most of which are

well known within gaming culture and especially retro-gaming.Where MaSu’s other songs are largely influenced by computer game

soundtracks,

in this instance a relationship between MaSu and gaming is made explicit by

the band covering these well known themes. Discussions of these instrumentals

triggered talk about the games whose music was featured in the medleys. To

discuss the ‘Sidology’ tracks is to implicitly discuss gaming culture.

For a long time, MaSu’s

unofficial FAQ included the unanswered question “Where is Sidology Episode 2?”

The official explanation was that the song was not yet good enough to be

released. Fans on the forum almost anticipated this song almost as much as the

release of RDR, because its release completed a trilogy that had been

presumed abandoned. There were speculations, even requests, as to which

computer game excerpts would appear in the medley when finally released.

‘Sidology Episode 2: Trinity’ was finally released the day ‘www.hubnester.com’

opened. Hubnester is the name of the band’s front organisation, through which

they distribute all their merchandise. Upon the release of ‘Trinity’, a thread

appeared in the forum discussing which computer game themes were identifiable

in the medley. Robert eventually declared which themes were present, however

the fans were not satisfied with just this information. They then attempted to

identify where the individual game tunes featured in the ‘Trinity’ medley as

they had done with the previous ‘Sidology’ tracks. In ‘TRINITY OUT’, the track

was broken down into detailed sections as seen below/overleaf:

Supremacy

(0:00-3:59) (?)

R-Type

(4:00-5:50)

Skate or

Die (5:51-6:15)

<missing>

Zelda

(6:48-6:49)

<missing>

Last Ninja

2 (7:10-7:59)

Metroid

Prime (8:00-8:15)

International Karate (8:16-10:22)

Turrican

Loader (10:21-12:09)

Metroid

Prime (12:10-12:50)

The fans here demonstrate a

form of textual analysis, identifying which notes in ‘Trinity’ came from where

in computer gaming history. In order to participate in such a practise, a firm

knowledge of music from the ‘retro’ era of computer gaming history is

necessary. In order to appreciate ‘Trinity’ as a medley and not just an

instrumental, the end-user must be acquainted, either through having played or

having heard, the games whose music features in ‘Trinity’. Games like Last

Ninja 2, R-Type and Turrican Loader are all from the late

eighties and early nineties. In order to understand the significance of

‘Trinity’, it is necessary for an end-user to know these games. The

‘Sidologies’ explicitly reference the retro-gaming sector of wider popular

culture.

The band, being fans of gaming

themselves, had released a riddle with the release of ‘Trinity’ that their fan

base took to solving. The same vernacular knowledge of computer gaming was

required of the MaSu fans as the band themselves in order for this puzzle to

be accepted and completed. In this instance, MaSu too are fans of the

same discursive entities that their fan base also warms too. On the MaSu

forum, the homogenous interest in gaming from both the band and their fan base

means that between the two groups, a new object and, correspondingly, a new

level of fandom is created in which the producer and consumer are no longer

segregated. Just as fans can be fan/producers (to adopt a Hillsian dualism)

via the production of fan texts, we must acknowledge the existence of the

producer/fan too.

The band has admitted on

several occasions to being fans of anime and other types of animation. In the

thread ‘Film And TV Shows’, discussions of anime often show up among the fan

base, as well as other TV programmes and films. Because some of MaSu’s fans

are fans of anime too, we see compatible levels of fandom emerging between the

interests of both the fans and the band. When textual producers and their fans

share a fan appreciation for a work non-analogous to the producer’s creative

involvement, they can create a combined or joint fandom. This concept builds

on what Nancy Baym calls ‘joint projects’. As she notes:

In online communities, as in many offline communities, joint projects manifest

through the topic around which most discussions revolves. Despite its

centrality, topic is a woefully understudied influence on an online community

(Baym, 2000: 137).

Threads like ‘Film And TV

Shows’ allow for multiple fandoms to be occurring simultaneously, in which the

producer is not necessarily exempt from the social discourse of fandom. Within

this thread, it is entirely possible for MaSu to be participating in fan

discourse on their own forum. The creation of ‘Trinity’ makes explicit MaSu’s

fan status in relation to gaming.

Whilst band/fan hierarchies on

the forum do not suddenly ‘break’ because the object of discussion can switch

away from the band to gaming or anime, they can undergo a temporary process of

reformulation. Depending on what the object of fandom is, alters the social

discourses surrounding it in terms of band/fan relations. Fan studies have

well examined how fandom can be hierarchised vertically. In doing so though,

this ignores the horizontal reality that multiple fandoms can occur at the

same time, exemplified by the ‘Sidology’ medleys. Thinking along this

trajectory opens up a simple but overlooked question within Fan Studies, not

possible in the vertical model: ‘Would any band produce music if they were not

first fans of music themselves?’ The idea that you are no longer a fan

if you shift into a ‘producer’ discourse is poorly conceived and not one that

is evidenced on the MaSu forum. The advent of financial profit does not make

you less a fan.

With the distinction between

band and fan as totally segregate discourses now problematised, and having now

established that multiple fandoms can occur within an online social space

around multiple discursive objects, the question now raised is ‘what is there

on the forum that can be said to be culturally specific?’ This I shall detail

in the next section.

HYPER-REALITY AND THE EMIC/ETIC

DIVIDE

Nancy Baym, in ‘Tune In

Tomorrow’, notes the popular conception of “the social loser who can only make

friends online is in many ways quite similar to that of the soap opera viewer

who watches because the characters are easier to befriend than are neighbours”

(Baym, 2003: 241). But where a soap world is unreal, the Internet is

hyper-real, a simulacrum of the outside world encouraging end-user

interactivity with other (cyber) selves, unlike in the soap. As she further

notes; “[p]articipants’ interests and concerns oft reflect those that matter

to them offline” (Baym, 2003: 241). In the case of the MaSu online community

however, it is not the offline world that brought the folk together. MaSu’s

music was accessible initially only through the use of the Internet. It is a

case of the hyper-real filtering into the real, not the reverse. Which is the

‘dominant’ text, the live or the mp3, is an issue I asked the band for

clarification on:

[S]eeing a band live is an experience that can even change your view of music as a concept, and above all certainly your view of a certain band. I do believe however

that some fans are not the concert type and get the most out of the music while listening on mp3s on their computer.

Whilst one of the appeals of

Ethnography is its lack of reliance on a priori hypotheses (Hine, 2000:

42), a major methodological issue within any ethnographic approach is

identifying what elements of a culture are specific to it, and which elements

are culture-free, for which we do need some theoretical tools. William

Sturtevent, in ‘Studies In Ethnoscience’, divides cultural characteristics

into emic and etic categories. The emic qualities of a culture are those that

are specific to it, whereas the etic qualities are those which are culture

free, usually belonging to wider culture (Sturtevant, 1972: 133 – 135). From a

post-modern perspective, the idea that there can be anything ‘culture free’ is

extremely problematic, for even the language we use in day-to-day life

contains culture within it. Following the post-modern turn, in which concepts

such as the self, identity, culture and society have become fragmented, new

communication technologies further blur the line between the self and society

(Dodge & Kitchin, 2001: 21). For Christine Hine, the Internet is an “‘anything

goes world’, where people and machines, truth and fiction, self and other seem

to merge in a glorious blurring of boundaries” (Hine, 2000: 7). With this in

mind, how are we then to distinguish between what is etic and emic? Is an

end-user’s avatar an emic or etic cultural characteristic? If it is specific

to the MaSu forum, then it could be considered an emic quality, but if the

avatar contributes to the identity of the cyber-self outside just the forum,

it could also be considered an etic quality. Moreover, is it the avatar image

itself that is an etic quality, or the coding language that is used to make

the avatar appear? Coding language like HTML, XHMTL, JAVA script creates the

etic boundaries, because without such coding ‘virtual realities’ and their

corresponding communities cannot exist. Within the hyper-reality of the

Internet, the meaning of etic is in doubt, for it can be applied in many

different ways when the cues of offline reality are filtered out.

Similarly, with emic qualities,

we are posed with a similar problem. I hold no pretensions about solving the

etic/emic paradox where virtual ethnography is concerned. However, I propose

that on MaSu’s forum, we can see emic cultural characteristics designated

through certain HCMC discussions. For example, let us imagine a newbie asks

“what is Sid?” This is one of the most commonly asked questions about MaSu, so

much so that responses to it by other end-users are highly predictable:

- A recommendation to use the

‘search’ feature on the forum to see if such a question has been asked

before.

- The newbie will be

re-directed to the unofficial MaSu FAQ or MaSu’s Wikipedia entries.

- A genuine answer will be

provided, usually with the suggestion to consider options 1 and 2 in future.

I suggest that ‘the obvious

newbie question’ in-fact implies the location of certain emic types of

knowledge within the forum. Through identifying which topics occur the most,

and which issues occur most frequently in discussion, we might begin to be

able to understand what is culturally specific to MaSu and what is not. MaSu’s

unofficial FAQ, for example, answers many of the most commonly asked questions

about the band, which are all highly culturally specific but do not belong to

wider culture.

One thread, ‘The Newbies Guide

To Frequent Topics’, came about at the suggestion of various end-users that a

thread be created to stop similar topics being reposted again and again. The

topics covered here are often similar to those covered in the unofficial FAQ,

but here they relate exclusively to the vernacular of the forum. Within this

thread are links to several other sub-threads on common topics. When a topic

recurs so often as to warrant inclusion in either the unofficial FAQ, or a

thread such as ‘The Newbies Guide To Frequent Topics’, it is important within

the community because of its cultural specificity.

Two problems present themselves

within the ‘common topic signifying emic cultural characteristics’ theory:

- The volume of this